|

The

Spread of Buddhism Among the Chinese

During

the third century B.C., Emperor Asoka sent missionaries to the northwest

of India, that is, present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. The mission

achieved great success as the region soon became a centre of Buddhist

learning with many distinguish monks and scholars. When the merchants

of Central Asia came into this region for trade, they learnt about

Buddhism and accepted it as their religion. By the second century

B.C., some central Asian cities like Kotan, has already become important

centres for Buddhism. The Chinese people had their first contact

with Buddhism through Central Asians who were already Buddhists. During

the third century B.C., Emperor Asoka sent missionaries to the northwest

of India, that is, present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. The mission

achieved great success as the region soon became a centre of Buddhist

learning with many distinguish monks and scholars. When the merchants

of Central Asia came into this region for trade, they learnt about

Buddhism and accepted it as their religion. By the second century

B.C., some central Asian cities like Kotan, has already become important

centres for Buddhism. The Chinese people had their first contact

with Buddhism through Central Asians who were already Buddhists.

When the Han

Dynasty of China extended its power to Central Asia in the first

century B.C., trade and cultural ties between China and Central

Asia also increased. In this way, the Chinese people learnt about

Buddhism so that by the middle of the first century C.E., a community

of Chinese Buddhists was already in existence. As

interest in Buddhism grew, there was a great demand for Buddhist

texts to be translated from Indian languages into Chinese. This

led to the arrival of translators from Central Asia and India. The

first notable one was Anshigao from Central Asia who came to China

in the middle of the second century. With a growing collection of

Chinese translations of Buddhist texts, Buddhism became more widely

known and a Chinese monastic order was also formed. The first known

Chinese monk was said to be Anshigao's disciple.

The early translators

had some difficulty in finding the exact words to explain Buddhist

concepts in Chinese, so they often used Taoist terms in their translations.

As a result, people began to relate Buddhism with the existing Taoist

tradition. It was only later on that the Chinese came to fully understand

the teachings of the Buddha.

After the fall

of the Han Dynasty in the early part of the third century, China

faced a period of political disunity. Despise the war and unrest,

the translations of the Buddhist texts continued. During this time,

both foreign and Chinese monks were actively involved in establishing

monasteries and lecturing on the Buddhist teachings.

Among the Chinese

monks, Dao-an who lived in the fourth century, was the most outstanding.

Though he had to move from place to place because of the political

strife, he not only wrote and lectured extensively, but prepared

the first catalogues of them. He invited the famous translator,

Kumarajiva, from Kucha. With the help of of Do-an's disciples, Kumarjiva

translated a large number of important texts and revised the earlier

Chinese translations. His fine translations are still in use to

this day. Because of political unrest, Kumarkiva's disciple were

later dispersed and this helped to spread Buddhism to other parts

of China.

The Establishment

of Buddhism in China: From

the beginning of the fifth century to around the end of the sixth

century, northern and southern China came under separate rule. The

south remained under native dynasties while the north was controlled

by non-Chinese rulers. The Buddhist in southern China continued

to translate Buddhist texts and to lecture and write commentaries

on the major texts. Their rulers were devout Buddhists who saw to

the construction of numerous temples, participated in Buddhist ceremonies

and organised public talks on Buddhism.

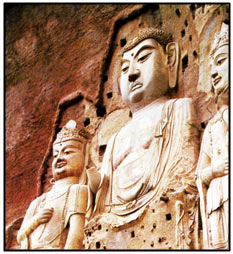

In northern

China, except for two short periods of persecution, Buddhism flourished

under the lavish royal patronage of rulers who favoured the religion.

By the latter half of the sixth century, monks were employed in

government posts. During this period, Buddhist art flourished, especially

in the caves at Dun-huang, Yun-gang and Long-men. In the thousand

caves at Dun-huang, Buddhist paintings covered the walls and there

were thousands of Buddha statues in these caves. At Yun-gan and

Long-men, many Buddha images of varying sizes were carved out of

the rocks. All these activities were a sign of the firm establishment

of Buddhism in China by the end of this period.

The Development

of Chinese Schools of Buddhism: With

the rise of the Tang Dynasty at the beginning of the seventh century,

Buddhism reached out to more and more people. It soon became an

important part of Chinese culture and had great influence on Chinese

Art, Literature, Sculpture, Architecture and the Philosophy of that

time.

By then the

number of Chinese translations of Buddhist texts had increased tremendously.

The Buddhist were now faced with the problem of how to put their

teachings into practice. As a result, a number of schools of Buddhism

arose, with each school concentrating on certain texts for their

study and practice. The Tian-tai school, for instance, developed

a system of teaching and practice based on the Lotus Sutra.

It also arranged all the Buddhist texts into graded categories to

suit the varying aptitude of the followers.

Other schools

arose which focused on different areas of the Buddha's teachings.

The two most prominent schools were the Ch'an and the Pure Land

schools. The Ch'an school emphasized the practice of meditation

as the direct way of gaining insight and experiencing Enlightenment

in this very life. (see link)

The Pure Land

school centres its practices on the recitation of the name of Amitabha

Buddha. The practice is based on the sermon which teaches that people

could be reborn in the Western Paradise (Pure Land) of Amitabha

Buddha if they recite his name and have sincere faith in him. Once

in the Pure Land, the devotees are said to be able to achieve Enlightenment

more easily. Because of the simplicity of its practice, this school

became popular especially among the masses throughout China.

Further Development

of Buddhism in China:

In the middle of the ninth century, Buddhism faced persecution by

a Taoist emperor. He decreed the demolition of monasteries, confiscation

of temple land, return of monks and nuns to secular life and the

destruction of Buddha images. Although the persecution lasted only

a short time, it marked the end of an era for Buddhism in China.

Following the demolition of monasteries and the dispersal of scholarly

monks, a number of Chinese schools of Buddhism ceased to exist as

separate movements. They were absorbed into the Ch'an and Pure Land

schools which survived. The eventual result was the emergence of

a new form of Chinese Buddhist practice in the monastery. Besides

practicing Ch'an meditation, Buddhist also recited the name of Amitabha

Buddha and studied Buddhist texts. It is this form of Buddhism which

survives to the present time.

Just as all

the Buddhist teachings and practices were combined under the one

roof in the monasteries, Buddhist lay followers also began to practice

Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism simultaneously. Gradually, however,

Confucian teachings became dominant in the court and among the officials

who were not in favour of Buddhism.

Buddhism generally,

continues to be a major influence in Chinese religious life. In

the early twentieth century, there was an attempt to modernize and

reform the tradition in order to attract wider support. One of the

most well-known reformist was Tai-xu, a monk noted for his scholarship.

Besides introducing many reforms in the monastic community, he also

introduced Western-style education which included the study of secular

subjects and foreign languages for Buddhist.

In the nineteen-sixites,

under the People's Republic, Buddhism was suppressed. Many monasteries

were closed and monks and nuns returned to lay life. In recent years,

a more liberal policy regarding religion has led to a growth of

interest in the practice of Buddhism.

Chinese

Buddhist Links:

|